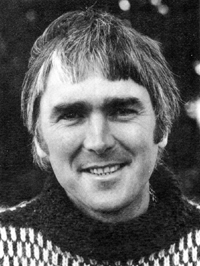

Earlier this year (the 23rd August 2017) I went to visit Roy Nevitt and his wife Maggie at their house in Stony Stratford, Milton Keynes. Roy moved to the town in 1967, initially to work as a lecturer in drama at North Bucks College of Education situated in Bletchley Park. After two years there, three and a half years in the USA, and eighteen months as Director of Drama at Wanstead High School, he returned to Stony Stratford and was appointed Director of Drama at Stantonbury Campus where he began to build up community drama in the new city. His wife Maggie worked alongside Roy, becoming Advisor to the Milton Keynes Foundation in 1989, and then Arts Consultant to the Community Trust. Most of the interview was with Roy, as it was he that was the writer (and director, and producer) for the majority of the community theatre work that was made during this time; but Maggie had many insights to share as the interview progressed.

This is a long interview, but it’s one that I think gives a fantastic overview of the work of one of the earliest pioneers of the community theatre movement, and of a period when theatre was viewed, and financially supported, as an important tool of community building on a strategic level. And it also gives a real insight into the crossover of a variety of theatrical forms, and of the movement from a decidely political impetus to a situation that many people will recognise today.

Roy, can you begin by telling me a little about the first play that you made here? Where did the idea come from – the notion of making a play of this type? And what was the function of the project and script?

I think the root of it all was when I was attending a drama course at Keele University with Peter Slade in 1965, prior to taking up a post of Head of Drama in a comprehensive school in Shropshire. The nearest professional theatre to Keele was the Victoria Theatre, Stoke on Trent, so on a free evening I wandered into Stoke looking for a play and I walked right into Peter Cheeseman’s ‘The Staffordshire Rebels’ and it blew my mind. It was so exciting. It was telling the story of the English Civil War as it took place precisely in that area of North Staffordshire. It had humour, colour, energy, history; and it was a documentary play. He’d done this with twelve dedicated professional actors, people like Ben Kingsley and Robert Powell; he had actors of that quality performing in this wonderful homemade documentary. And I was thinking – and this is really near the beginning of my career as a drama teacher – ‘bloody hell! I could do this!’ But being an educator I would want students in it, I’d want to have them involved in every stage of it. But I’d also want to have my colleagues on the teaching staff involved in it; and I’d want to have their parents involved in it. I’d want it to be a community play.

So that settled in the sands of time really because I had too much other work to ever do such a thing at that stage. The next thing that triggered it was when I was in Dillons bookshop in London, just browsing with some time to kill, and I picked up a book by Bertram Edwards called ‘The Burston School Strike’. And it was an extraordinary book, full of documents that had arisen from the historical event of a school strike that happened in the Norfolk village of Burston in 1913. The strike was triggered because of huge injustice by farmers and church people and landowners, who were on the governing board of this school, to the teachers whose only offence was that they loved the children. They demanded justice for the children, boots for them to wear rather than walking through snow barefoot, coal to put on the fire so they didn’t have to freeze to death during their lessons; and for farmers not to be allowed to take them out of school to pick up stones from the fields or frighten crows away as part of the agricultural season. So these teachers, because they had the children’s interests at heart, and a general liberal sense of education, were unpopular and they were twice sacked; once in a previous school and then subsequently in Burston, a village about two miles from Diss in Norfolk. Now Bertram Edwards had been incredibly excited when he found out about this historical event and couldn’t understand why it had been forgotten because it was a tremendous story. The school went on strike, and the kids went on strike supported by their parents to such an extent that they built a strike school on the village green. It started in 1917 I think, and stopped running in 1939. And we went to see the school and it still had all the names of all the trade unions that had supported it stamped on the side of the building, although now it was just a furniture store or something.

I befriended Bert and asked ‘can I make a play of your wonderful book?’ and he said it’s what he always dreamt would happen, that there would be a play; and he introduced us to the people who were still living (now in their seventies) who’d been children at this school that had gone on strike. A principal one of those was a woman called Violet Potter; and Violet, aged fifteen – when Mrs Higden the headteacher had come in to say that she and Mr Higden would no longer be their teachers because they’d been dismissed from their post – Violet walked to the front of the class and wrote on the blackboard ‘we are going on strike tomorrow’. And I knew I had the end of my First Act right there, with her writing that on board.

The Strike School was opened with a big event with dancing and singing and speeches and trade unionists and so on, and the central speech was by Sylvia Pankhurst which I was able to find verbatim; and she said things like ‘whose feet would not dance on a day like today?’ And this fabulous celebration of the power of people to confront blatant conservative injustice and protect the interests of children and education was there in that historical event.

Having got to know Violet, and all these other striking children that were still alive, we got permission to take our play in its draft form and perform it in situ in all these bits of Burston village. The school scenes were performed in the school, and the church scenes in the church, and the field scenes were out in the fields and so on. They got so interested in our telling of their story, we from Milton Keynes telling their story in Burston, that they all came in buses to see a matinee of our performance when it was finished and complete. There’s a moment at the end of the play when our actress, who was a fifteen year old girl playing Violet Potter, had to make her speech saying ‘I declare this school open and to be forever a school for freedom’. And on that particular matinee, with Violet Potter sitting on the front row of a theatre in the round stage, this young actress reached out and lifted up Violet Potter, the real one, who aged seventy something spoke the words that she’d originally spoken on that day. For me that was the absolute proof of the spirit that runs through these kinds of plays if they’ve remained true to their source material. If the characters as performed by the actors are true to the people they are representing, so much so that the real people in the audience will tell you ‘that’s exactly what happened’. We know it wasn’t exactly what happened; that when people say ‘I saw my father on the village green shouting that speech like that’, you know it can’t have been precisely like that. But they feel it was like that so there’s a ring of authenticity running through this kind of stuff; and the proof is that the people whose stories are being told tell you that you’ve got it right. And what was the year of that play?

And what was the year of that play?

It was 1974; no actually the performance was in 1975.

You said the inspiration was seeing Peter Cheeseman – in terms of an idea of the style – and that you said you thought you would expand that idea so that it wouldn’t be with a professional cast but that it would be a ‘community play’. I’m wondering what the notion of a ‘community play’ was in 1974, because I know that my notion of a community play comes from a later period actually, which is the Ann Jellicoe moment about four years after that. So I’m wondering what your reference for the ‘community play’ was.

Well OK, I wasn’t coming to it with a notion of what a community play was; I was coming to it from the grass roots, the bottom up. I wanted a play where I could have thirty children performing alongside God knows how many adults. Let’s say forty adults and thirty children, with the adults being my fellow teachers and the parents of the children and other members of the community. These are the people I wanted to work with on such a project.

And why did you want to work with them? Because they offered you raw materials to do a big play or for another reason?

Well partly … yes partly because they became as passionate about it as I did. My colleagues wanted to use it, and the work we were doing and the document stuff, within the curriculum; this fitted in exactly with them. The Open University got terribly excited by it all and made it into a perfect example of curriculum development within a secondary school, and published papers on that which became course materials for their students.

So was this a time when the idea of local history and people’s history in the education sector was quite big?

Stantonbury was a unique kind of school. When we moved here for the second time we were coming into a situation where four towns and thirteen villages, with forty thousand people, was going to expand into a new city with a million people over a period of time. And my role at Stantonbury was Director of Drama and Theatre, but I was first of all paid by the Development Corporation whose responsibility was to build a city. And they chose to pay me because they wanted someone to advise them on theatre in a new city context; but they left me with total freedom to do whatever I wanted. So I said ‘I want to be based in a school campus with a professional theatre’, and if I could work from there then I could do everything that they would want me to do in terms of growing drama and theatre from the grass roots. And so a community play like the one I’ve just described, which was the first one, had this effect of involving people who’d lived here for ever, but also including all these people who were just arriving from Belfast, Glasgow and London to come into the new city. So that fusion of two communities, who had to learn to live together, around a creative project like the making of a new play; and the performance of it to an audience, and then even extending to being an audience for that kind of thing, was met by this kind of play. We were largely involved in education but we were also involved in community development, in a situation that had to have community development if it was going to be a successful city.

And that was why they employed you I presume?

Yes; Bucks County Council quickly saw my value and took over my salary. But I was able to stay with complete autonomy over my work for the next twenty seven years. And the theatre was such that I was teaching kids in the theatre in the daytime, I was rehearsing community people in the evenings and Sundays, and we were promoting professional theatre on Thursday, Friday, and Saturday. And so we had access to professional theatre practitioners who would run workshops with whoever was our cast in our current play; kids and adults could all work with people like Mike Alfreds and his company Shared Experience; and there were numerous ways that they could get close to productions by Joint Stock, Hull Truck, Belt and Braces, 7:84 and many others, who were bringing their plays into our theatre in any particular week, helping Front of House, backstage and participating in workshops run by some of these companies.

And when you wrote The Burston School Strike was that the first play you had written or had you written anything before? And what did you use as a reference point as you were trying to write something that was different?

I had written some things before with Gordon Vallins, who was at the Belgrade in the great Belgrade T.I.E days. He was my colleague at North Bucks College of Education when we were training teachers and we’d written a so called documentary play about America in the year of the presidential election … it must have been 1968. I won’t go into a lot of detail about that but it was a kind of fake documentary in my book because it was all derived from secondary source materials, like the Warren report over the assassination of Kennedy and so on. A true documentary goes to primary source materials, and must do. So our primary source materials for Burston were the actual people who had lived the experience; and the letters that were written; and the minutes of meetings that were preserved.

Now on the back of that, because the play had been so successful locally, the Development Corporation commissioned me to write another community play, but on a local subject; it had to be about somewhere here. I think they gave me two thousand quid as a commissioning fee, which was quite a lot in those days, and I used it entirely to pay a researcher. We had several volumes of good local history books by a man called Sir Frank Markham who had been MP for this Buckinghamshire area, and he was a good enough scholar to have put footnotes and notes at the end of chapters saying exactly where he got his source material from. His own narrative of the history that he was telling was in the voice of a cultured, educated, serious member of the community; but that was no good to us – that’s the secondary source material that I didn’t want anything to do with. But it told us where to go for the primary source material. So I sent the researcher, Margaret Broadhurst, to the House of Lords records office; I sent her to the National Transport Records office; to the Bodleian library; wherever there was a document that revealed what was going on in the particular story that we were interested in.

We didn’t know what the story was going to be when we started researching. We knew it was going to be about Wolverton, which is a railway town, one of the four towns that existed before Milton Keynes enveloped it all. We started collecting right from Domesday up to the present day and we had shelf loads of filing boxes with the documents that we’d managed to collect. It would have been a terrible pageant if we’d gone down that road but there was a period, 1830 to 1865, where every file was packed with wonderful material about the railways and their arrival. I’d sent Margaret to the Northampton newspaper records, and there were two newspapers in Northampton in the nineteenth century. One was a Whig newspaper and one was a Tory newspaper and you had completely opposing views in conflict with each other every week of what the railways meant to people. Which is one of the essential drama tools, to have those opposing, conflicting points of view. One paper would say the railway was a great moral teacher; it would teach the value of punctuality, ‘because what purpose would it do you to arrive at a station ten minutes after the train has left’? And then the other one – the landlords side of the story – was saying ‘these trains are ghastly machines crossing our land belching this vile smoke, making all this noise and scaring our horses’. And so we had all this stuff in pure original primary source material form; and it was Peter Cheeseman, who we engaged as consultant to the writing of the play, who helped me see clearly what the structure should be.

Basically it’s going to be a chronology; it’s got to have a really great moment to finish the first half, and then it’s going to have a second half and it’s going to have a great ending. And it’s going to be basically constructed as a scene, followed by a song, followed by a scene, followed by a song. And the scenes would have, as the spoken utterance of the actors, primary source material. But the songs could be more reflective and contain more generalisations and be more … transcendent if you like.

But of course it’s going to be converted into … well let me tell you my method of really pinning down a dramatic script that’s come from a load of documents. I want to know the answer to six questions, and they’re all ‘w’ questions. I want to know ‘Who?’ – and they’re the characters. And if you look at your documents they’re about people. You know it’s this Lieutenant General who’s giving evidence to the House of Lords enquiry over the railway question and whether he as a military man wants railways or not; and he says he’d rather his soldiers march than go by railway unless there was an emergency, like a riot somewhere in Liverpool in which case he’d love the railways – and so we’ve got a character there. So the ‘who’ question gives you the people, the characters, and they’re real people who had real lives and who spoke words that have been recorded in real situations.

The next one is ‘Where?’ You want a physical location to play this scene, a strong sense of place. Are they inside; are they outside? Are they around a table; are they in a field? Where is it? Is it a fight between the railway navvies and the canal navvies? And so is it on a canal bridge? Where is this ‘where?’ location.

‘When?’ You want a specific time; to pin it to the time of day. You want a sense of which year it was and how it relates to other events.

‘What?’ is the action – what is going on here? It gives you the action of the scene and that’s essential to it obviously; what are they doing?

‘Why?’ is that great question. Good theatre directors always ask an actor to do nothing unless there’s a motivation to do it. You can’t even move unless there’s a reason to move; unless you want something; you want to gain something; you want to get something; you want to achieve something. That’s what makes you do it and that’s what makes you speak; that’s what makes you say those precise words in that precise tone of voice. So the why? is the motivation.

And then of course the sixth one is a bit of a joke really but it’s the ‘Weather’. So often a scene in the pouring rain with umbrellas is interesting. Or if its freezing cold with everyone all wrapped up in blankets, or sweltering in the sun. And so that’s how you get the business of each episode down on paper in a dramatic form – using those questions – and as I say then it’s about how you link the scenes together.

Then there’s the obvious statement that these plays are not pretending to be true, even though they’re documentaries based on primary source material and real people. They’re not true but there’s a feeling for truth in them. They’re actually works of art; they’re fictions because they’ve been constructed. There’s been a process of selection to decide what to include and what not to include. There’s been a process of juxtaposition to get the tension that arises from that happening immediately after that, or in relation to that. So this scene which is packed with humour follows that one which was deadly serious and gives the audience a little relief from all that concentration; which is one of the things the songs do as well. They give the audience a refreshment, having concentrated on one scene before concentrating on another.

So you’ve got the story and you’ve got the things you want to do in each episode to make it as theatrically interesting and engaging and affecting as possible. When selecting the scenes are you also aware of any contemporary concerns or issues that make you go ‘we’ll choose this bit of the story because, for instance, there’s an argument about a motorway or something’. Do you know what I mean? So that there’s a contemporary awareness …

Absolutely. I’ll give you two responses to that question. On the one hand generally speaking we found that we were telling a story about the invasion of newcomers into an existing population and the tensions that arise from that. In ‘All Change!’ we placed it in the 1830’s to 1860s when the railways came and all these people cascaded in to Wolverton to build the railways, and build the new town of Wolverton and live in it. So that parallel experience with our contemporary experience of what was happening with Milton Keynes was in general what we were doing with the whole play.

A specific example of how I might answer your question is around two main characters in the play – James McConnell who was our railway superintendent, in charge of the works at Wolverton, who was a kind of hero in our play really because of the kind of things he achieved. He built a science and arts institute which was giving genuine training to workers; and he built the Bloomer steam engine. And he was also the guy who cracked the problem of metal fatigue. He wondered why so many axles on the trains that were being built were breaking and causing accidents. And he realised it was because they were solid axles, and that the constant pressure near the wheel onto a solid axle changed the nature of the metal from a fibrous material into a crystalline material, and the moment it became crystalline it snapped. So he invented the hollow axle and those never snapped because somehow they transmitted the vibrations along the axle without that change in the structure. So we were kind of locally proud of our James McConnell.

But there’s another guy in the play called Richard Moon and he’s the Chairman of the London and North Western Railway Company. And he based himself in Crewe and nurtured a little engine called the Watt engine. It was small, it was light, it was fast and it was cheap and it didn’t last. But Moon’s philosophy was to make as much money as possible for the smallest outlay. McConnell’s philosophy in Wolverton meanwhile was to make things of magnificent craftsmanship, built so they’d last forever and beautiful to look at. Now for me as a dramatist the best thing I did was go and meet Reverend Awdry, who is the Thomas the Tank Engine man and knew all about James McConnell. He gave me a priceless account of a race against time that was occasioned by an event in the American Civil War, where a British ship had been attacked and hijacked with the result that the British government demanded that if the crew and ship weren’t released immediately that Britain would go to war against America. Now the message was sent from America that the crew had been released; but if you think about it that message had to cross the Atlantic by boat to Ireland; had to get on a steam packet and go around Ireland to Anglesey; and then it had to get on a railway engine from Holyhead to Stafford, so there was a need for the train journey to be made as quickly as possible to reach the Houses of Parliament before war was declared. There was a time pressure on it. And Awdry had collected the exact timings of that race from Holyhead to Stafford and all the conditions that prevailed. The first part of the journey was made with the Watt engine and then at Stafford the message was transferred to a Bloomer engine which would make the next stage to Euston, coming right through Wolverton, coming right through our midst here. And we had the timings of that.

They came out of the Kilsby tunnel into dense fog, which slowed it down, but then it built up speed again; the fog cleared at Tring and they were doing seventy miles an hour into Euston and they got the message there with two minutes to spare. And the performance of the Bloomer engine was superior over the distance to the performance of the Watt; so the Wolverton engine had won over the Crewe engine and McConnell had won over Moon. Now that provided the finale, that race of the two trains, with two guys on the engine and the narrative being spoken. We actually got two railwaymen to talk to us and recreate that journey in their imagination. We asked them questions like ‘in the dense fog how do you know where you are?’ and they’d say ‘sound. There’s a quality. If you’re going through a cutting you know exactly that you’re going through a cutting. If you’re in an open field it’s a different sound; if you’re going through a tunnel obviously you know where you are’. They taught us how to shovel coal authentically, and what the driver is on the lookout for at all times. So we staged it on the basis of their input.

I mentioned earlier, in terms of structure, about having a great ending for the first half and a great ending for the second and that was our ending for the second. But for me these are Thatcher’s days, you know. There are arguments about what the nature of work is today? Is it something we should be proud of? Should we have a lifetime job? Should we be craftsman? Should we be refining our skills to perfection? Should we be encouraging our young people to train for these skills? Should we have apprentices? Should we be ingenious in our inventions? Should we solve problems like metal fatigue? Should ordinary people be able to do that? Or are we all about quick and easy; making a quick profit with the smallest possible investment; concentrating on the greatest possible profit and all that short termism which seemed to come in with Thatcher. And so we felt we were making a contemporary political point within the historical frame.

Was that something that you thought ‘it’s in the text, it’s in the historical moment, it’s an implicit understanding, the audience will get it’? Or did you think ‘I want to make it a bit more explicit?’

No, it was the first; implicit and trusting the audience to make the connection.

And did they?

Well one might make a little programme note, drop a hint or two for them to look for it.

I don’t know if you know Punch magazine; I don’t think it’s published anymore but it’s a priceless magazine. We found this edition where Mr Punch took a train from London to Wolverton, and he stepped out of the train at Wolverton and had eleven minutes to go into the refreshment room to get some soup to refresh him before he continued his journey to Birmingham. And there’s another document in a book we found called ‘Stokers and Pokers’ – these are firemen for the railways and it was a book about them, but it included data about the Wolverton refreshment room that Mr Punch entered. We know that there was a laundry maid, a scullery maid, a kitchen maid, and a housemaid on duty. There was an ‘odd man’, and a matron to guard the reputation of the girls who worked in the refreshment room against the attentions of predatory males who would get off the train. All these characters who we were able to put on the stage.

We also discovered all of the food and drink that was available; the bottles of stout that were warmed up and all the cakes that are named in these lists. So we gave all this material to one of our songwriters who – having learned from Ewan (MacColl) and Peggy (Seeger), how to make any number of classic folk songs – chose to do what is called an accumulation song. So the verse told you ‘if you ever you take the railway that runs to Wolverton Town, three hours out of Euston the passengers set down’, and explains how you can get into this Refreshment Room. And then the chorus talks about the people and the jobs they’re doing and the food that’s available; and every chorus ends with ‘and a matron to guard their reputation’. And this just lent itself to an exquisite form of choreography to the song where of course, in the middle of it, Mr Punch steps down off of the train and enters the room where he’s got eleven minutes to get his hot soup. And when he’s served the soup, the steam, he says, ‘rose from the ladle and took the skin off my face’ as it was far too hot to eat. And having ordered and paid for the soup, and having had no time to drink it, the whistle goes and he has to get back on the train. So it was a wonderful dance with song and music; a really humorous way of ending the first half.

You mentioned that if the researcher hadn’t have found the boxes it might have been like a ‘ghastly pageant’.

I wouldn’t have done it then.

By pageant what do you mean? Just a collection of historical anecdotes from A to Z?

I’ll tell you something. There was a later play that we created entirely from the diaries of a local woman. She wrote the diaries from I think 1900 to 1920, something like that. Anyway she was an extraordinary woman and we wanted to write her play and tell her story because it was a Sister Play to a play about a boy soldier that we’d written, the Albert French story (‘Your Loving Brother Albert’). And Albert’s story, which ended in his death in France in the war, was in contrast to this girl’s story who stayed at home. Her diaries are full of bicycle rides; of dealing with men who try it on with her; of going to church and making fun of the vicars; of working in the sewing room of Wolverton Works and so on … it’s a wonderful story. But one of the things that she did with her friends was put on one of these pageants, put on these hospital fetes to raise money for the hospital up at Northampton. And their fete, parts of which we staged, was the kind of pageant that I didn’t want to make a hundred, a hundred and fifty years later. They were like Empire Day fetes; they had children dressed as leeks and patriotic songs.

You mentioned the days of Thatcher. Was there a sense that the emerging social and economic order was changing and in play? Were discussions about the changing ethos more prevalent in an educational setting? Was this in the ether and informing work?

Well it was really. I mean Wolverton had been a town with thousands of people building railway engines and over time that had reduced to a railway repair works, and then by the time Thatcher was around it was ‘will there even be a future for this great industry which had been the soul of the town?’

We were here to build an exciting new city which was born out of the Harold Wilson and Jennie Lee time in government and yet it entered the phase when Thatcher was in power. The Open University had been created at the same time in our town, in Milton Keynes, with the same idealism. And the idealism that made Milton Keynes what it is, because it’s still here and has survived everything, is about a belief in people and the talents of people and the dignity of people and people being worth total respect; and their right to work and earn a decent living and have a decent education.

We had the chance to create a new school from scratch at Stantonbury, and that’s where the theatre was and that’s where these plays were happening and that’s where the whole drama and theatre experience was being grown and developed; in a brand new school where we did things differently. We had no school uniforms; we had no punishments, because you didn’t need them. Everybody was on first name terms from the Director down to the youngest child and including the cleaning staff. It was a community itself, and adults could come into the lessons if they wanted to and they wouldn’t find the door shut. Now, twenty years after Thatcher, they’ve built gates around the school and you can hardly get in without unlocking a gate. And they’re all in school uniforms because there has been a change, and that change has been eating away at that wonderful idealism and that socialism which was present in the days when we created the school.

And was that a word that people used, socialism, back then?

Oh yeah, we were not ashamed of ‘socialism’ and still aren’t.

So socialism was part of the driving force of the whole experiment?

I would say so; and I would say it was for Peter Cheeseman in Stoke on Trent as well. A People’s Theatre; a theatre for people; a theatre about people.

Was there a sense that the theatre you were making was partly a political project in any way?

I told you that we got professional theatre companies in every week; who were those companies? Joint Stock doing ‘Fanshen’; Belt and Braces; 7:84, seven percent of the population owns eighty four percent of the wealth. Theatre of any quality was political in those days, and it was left wing.

And you saw the work that you were making being part of that family of left wing theatre?

Except we never started from an ideology. We started from source material, actuality; and it was the creative transposition of actuality into an art form that we were about.

Was it about the community that was created in the process of making the piece that was important, rather than what the piece was saying politically?

Yes. Well I think both are important. Sometimes we had to defend documentary theatre against some of our extremely radical friends in political theatre because we weren’t doing strident anti-Thatcher plays. We weren’t doing stridently, outspoken, manifestly political plays; that’s not the nature of a documentary play. But because you’re dealing with working class people as much as you’re dealing with middle class people, people can draw their own conclusions in the historical perspective about what kind of deal these working class people are getting and what kind of impositions these upper class people are making. If you look at that railway struggle, the wealthy people with the land were against the railways and tried to stop them and used everything they could to do so. And they only withdrew their opposition when they were extravagantly bribed by the railway companies to give up their opposition. But they were selfish and they wanted to maintain what they’d got; they were men of property and they didn’t want to lose any of it. Whereas you’ve got the working people whose lives were being transformed for the better because of the railways. They were getting decent jobs, regular jobs, jobs within which they they could unionise, jobs that had respect – a train driver had great respect, a fireman had respect, a signalman had respect – because they were skilled and were looked up to within their communities. So people in the audience could see that. They can draw their own political conclusions and you don’t have to distort; you never distort anything. But I admit that you do select.

So this is all happening in the mid-seventies onwards?

Mid-seventies to ninety was our heyday I’d say.

So at what point in this process … because you’re making these plays that you call ‘documentary plays’ that are involving the community …

We called them local musical documentary plays, but they’re community plays, yes ..

Then Ann Jellicoe starts doing her stuff down in the South West, are you aware of that?

We’re very much aware of that and we went to see one or two of them and we knew Ann.

How did you know Ann?

Well we knew her well enough at conferences to recognise her, or find out who she was and then have conversations with her about the respective work. I think she knew the work that we were doing and we obviously knew hers. We admired what she was doing, we were just aware that she was running an operation that would arrive in a town or village like the circus coming to town. They would stay and do a wonderful job of creating a play there and performing it there, and then they would go away again and it would be a different town or village that would get the next opportunity. And we knew that we were consciously doing something different from that in that we were here to stay, and we were growing our single community from within. And sure enough, over many years and many plays, everyone getting bigger and better in many ways, we were achieving that.

Was there any kind of conversational cross-fertilisation or observing these plays that called themselves ‘community plays’ that threw up suggestions for ways to work slightly differently? Or was your work going down a particular path?

Yes; I didn’t learnt anything from Ann’s work except that we weren’t the only ones that could make great community plays which would involve lots of local people of all ages and all characteristics, all occupations; and that they would all transcend themselves in that co-operative endeavour and do something, and achieve something beyond their wildest dreams. I think Ann could say that see achieved that. Jon Oram could say it and we would certainly say that.

And in terms of you going on to write shows, and the selection of the material, was it something that as it went on you thought ‘right, we’ve tackled this aspect of living in a developing city so we’re going to look at this aspect’? Or was it actually ‘we’ve found this story’ and it’s the story that was more important?

The second one was the Albert play, based entirely on Albert’s letters from the war. And the success of that led us to do something which we called ‘Days of Pride’; and by then we were wanting to include living memory. Having done ‘All Change’ which was set historically, with the only connection with living people in terms of providing spoken utterance for actors to use in was those train drivers and firemen that I talked about earlier, we now wanted living memory. And when we did ‘Days of Pride’ there were still people alive who had lived through the war, and so we were able to get most of our material first hand from the people who’d lived the experience.

The major character in ‘Days of Pride’ is an incredible story teller, Hawtin Mundy. He was a man who when we met him was blind and had been for some time but his memory was incredible for detail. His language was what I would call uneducated language, it hadn’t been channelled into the clichés and conventional speech that we all use but was the earthy, down to earth language which calls a spade a spade. His testimony of his experiences going through the First World War; through the Battle of Arras, the Battle of the Somme, being three times wounded and made a prisoner of war. He experienced everything first hand and had this vivid recall. He described what it’s like to be in ‘the valley of the shadow of death’ during battle and spoke in these biblical terms; because that was their literature, the bible, and so when he spoke with passion he spoke in those terms.

So we’ve got Hawtin’s complete testimony, against which we’ve got all of the documentary material we were able to collect from hundreds of other people who were alive then, and other documents that were discoverable from that time. And here we come to that political question once again. There was a terrific controversy in the newspapers of the time where the women at McCorquodales Printing Works in Wolverton, next to the Railway Works, were going on strike for more pay. They wanted a shilling a day or something, and the soldiers at the front were hearing about this and writing to the paper saying ‘what are these women doing? We’re standing in mud up to our necks for a shilling a day and there they are in the comfort of home going on strike. What’s going on?’ And a woman called Sis Axby spoke pure Women’s Lib; she gave the perfect case for why it was necessary for women to have some self-respect in their work and some adequate pay to live on. Of course they had sympathy for the men who were fighting but that didn’t mean that the womens struggle was not completely necessary and completely valid. And so the politics of Women’s Liberation and that whole struggle for the Suffragettes is there in the documents and make fabulous theatre, fabulous episodes within the play. So you’ve been on the battlefront with Hawtin in the Somme with all the explosions and events and incidents, and then you’re with Sis Axby back on the Home Front talking to a great crowd of women.

And you’re writing these?

I wrote Burston (‘The Burston School Strike’) and ‘All Change!’ I wrote Albert (‘Your Loving Brother Albert’) and then I included Roger Kitchen who was the co-director for the Living Archive (the three of us, with Maggie, were the co-founders) in the writing process for ‘Days of Pride’ because he was the one who interviewed Hawtin Mundy. Without Roger there would have been no documentaries from then on.

Roger was working on Days of Pride as a researcher?

He was. He lent me the letters for Albert so it was his gift of the letters that enabled me to write that one. And when it came to ‘Days of Pride’ it was the gift of his interviews with Hawtin, the soldier, that was so valuable. He would sit down at the table here with a typewriter, and we’d have the documents all spread out and the transcripts of the interviews at our disposal, and basically – I think it’s fair to say – I was the dramatist who knew how to make it into a dramatic scene, but Roger knew the material inside out. In the purest sense I was the dramatist involved in the writing and he was the provider of the raw material.

So you’ve written a number of plays now and is there a sense – and this might be a difficult question because it’s difficult to know in the heat of the moment never mind all those years ago – that you were more confident or more comfortable with it, or that you had settled on some kind of way of doing it, or that you were developing in some way?

We were … we were developing for a time. The one after ‘Days of Pride’, which was a tremendous success, was called ‘The Jovial Priest’ and it was about a notorious local priest. Again there was a lots of extant living memory that fed into building up the story. I thought that play had a weakness, which was that we were never able to get the story from the priest’s point of view; because it was all locked up in the church archives and they were buggered if they were going to let us have it. We had masses of hugely entertaining material, everybody else’s perception of this eccentric priest who was incredible. He used to come down a steep hill steering with his feet on the handlebars of his bike; he’d challenge anybody to a swimming race in the river; he went down to Eastbourne and did high diving off of the pier; he had a church with a congregation of two thousand and reduced it to just four. He was High Church, arrogant, fanatical, Donald Trumpist; an extraordinary man who alienated his entire congregation.

MAGGIE: At one point he called them all together and told them they were not married because the licence from one church had not been passed on to the one that they were in now; so everyone was living in sin. Well you can imagine how that went down.

ROY: And the ‘Jovial Priest’ was people’s nickname for him, an ironic, sarcastic term. But the documents that we needed to get hold of were in what the church calls the War Chest. It was all of the complaints against this vicar to the Bishop; and all those complaints exist, and all his ripostes were kept in this War Chest, and they just wouldn’t release them because they’re still embarrassed.

So without those what do you use instead for his … was he in it?

He was definitely in it.

So that character was created?

No; no we didn’t invent anything. A lot of it was action because we had an incredible number of descriptions of his behaviours so those were all staged. And we wove narrative into the dialogue, so quite a lot was conveyed through that narrative woven into dialogue.

But given the fact that he was such a brilliant character presumably you would want to create a …

I’d have to look at the script and see what words we put into his mouth because quite frankly I can’t remember. People did report what he’d said, what his sermons were all about and when he told his congregation that they were all living in sin that would have been derived from a document. The newspapers of the 1920’s and 30’s were verbatim; they would record verbatim things that were said, public speeches etc. So when I said we’d got nothing of the man himself I mean we’d got nothing personal from him; except that we knew his wife left him and so we staged that.

And the fact that you had nothing personal meant that you felt unable, within the rigour of your method, to invent that material?

That’s right.

Even though you wouldn’t have been inventing anything other than … you knew the situation but rather than put words into his mouth and create a character you wouldn’t do that?

That was the rigour that we worked from and I do see the point that you’re hinting at. I recently listened to Hilary Mantel talking about the historian and the creative writer and that wonderful tension that exists between the two; and she would have no hesitation, in fact it would be her purpose, to find out what was in the mind of this character and give him appropriate language. But we denied ourselves that. We made a play that was incredibly popular, partly because we introduced more popular musical styles and relaxed a little on the folk music thing.

Then with ‘Sheltered Lives’, again I would confess that it had weaknesses. It had a brilliant first half because the documents we found about the outbreak of the Second World War, and the events of the Second World War locally, were much richer than in the second half of the war . For example we had a wonderful source of letters written to his mum and dad by an evacuee who was placed in a house in Wolverton, and the stuff we got from those letters was incredible. We felt we had to get to the end of the war and we were doing scenes, because we’d found documents about things that were happening then, and when we looked back on it we wondered how we got away with the second half really. It just was weaker than the first half which is never a good thing.

MAGGIE: People like it.

ROY: They liked it but we were hyper critical of it. And certainly whatever we did we tried to make it dramatic; and it was enriched by music and we lifted it in every way we could through production and so on. But if you read it on the page I think you too would agree that this is a flawed play.

So the starting points always seem to be the discovery of some interesting source material that you then tell using an authentic source, using authentic voices as much as possible. You shape it; you use music to give yourself a breathing space to be less austere with your rigour; and then around that you involve as many people as possible. There are implicit connections you are looking for, or if there are stories that have a connection to the kind of contemporary identity or the current situation you may draw those out a little bit. Is there a sense over the years where you’re thinking ‘OK, we’ve now lived in this community for this length of time, we can see the way this community is beginning to bed itself in’ and that the awareness of this impacts on the choices of the stories? Or is it purely what lands in your lap?

I’ll answer in a personal way. Having got as far as … was ‘Sheltered Lives’ the last one that we did?

MAGGIE: No. It went Burston, ‘All Change!’, Albert, ‘Days of Pride’, ‘The Jovial Priest’, ‘Sheltered Lives’, ‘Nellie’ …

ROY: OK, so Nellie was the last one and then …

MAGGIE: We did ‘Nellie’ and Albert together …

ROY: We revived Albert. There had been a tradition of reviving a number of those plays, sometimes because we didn’t have the energy or the time to make another new one and it was time to bring one back because it had been so successful.

MAGGIE: We used to put them on every November you see …

ROY: And so quite often they got a second run, a play that had happened before. So that filled up the years. But to be honest there was a point when the creation of new ones was not something I wanted to do anymore. We came to a point where the churches asked us for one; we have an ecumenical tradition of churches in Milton Keynes and we were asked if we would do one to celebrate ecumenical church life. My response was ‘no, but we’ll do the Tony Harrison Mysteries for you, in three parts of ten performances each night; so you’ll get thirty nights of performance and it’ll be as good and as big and as colourful as the way that the National Theatre did it’. And so that’s what we gave them. We gave them a nativity at Christmas, Passion at Easter and Domesday in the Autumn; all within thirteen months. They had thirty nights of performance; stunning theatre, stunning music and involving the same people who had been trained through the documentaries …

MAGGIE: And a lot of the Christian Councils people as well …

ROY: And new people coming in all the time, because the whole project was growing like a mushroom.

So the people who are involved in it and are growing it are very much both people from the school, that are connected to the school, but also just community members who are invited in?

MAGGIE: Who invite themselves in. You get men and women and the kids coming along on Sundays, because you’ve got making workshops going on Sundays all day; and before you know it the kids are old enough to be in the plays. That’s how it develops.

So you’ve got a cast of what, a hundred?

ROY: Yes; quite often a hundred. But in a way the school was a community school. We ran a community college in the evenings and in a sense you could say all the work we did in the theatre was an informal branch of the community college, which was a pretty informal thing anyway.

You said that at the beginning your job was being funded by the …

Development Corporation …

That it was a development post in some way?

Initially yes …

Did that end?

Well no that stayed there because they asked me at one stage, early on, ‘what kind of theatre should we build in the city centre, to complete the city centre profile?’. And I said you don’t spend a penny on a huge theatre and make a white elephant when you’ve still only got maybe fifty thousand people around; you need a catchment of one hundred and fifty thousand at least to justify a theatre of the size and quality that we would like. And so the alternative was to invest in grass roots theatre all over the city. Obviously our theatre got huge benefits from it, and the music centres and the orchestras.

MAGGIE: And there were other small theatres on the campuses coming on stream so that you could develop a professional circuit.

ROY: We created what we called a Theatre Consortium, so we shared all our expertise; all these grass roots centres were working with the same purpose and with mutual support. By the time we felt we had a population big enough, and the passion strong enough in enough people to justify a big theatre, we started a Milton Keynes Theatre Development company to get one built. We had Branson’s money to build it until he suddenly fell out with his fellow investors over something and withdrew. So we were suddenly without a theatre again and yet the population was needing one and demanding one. Then the Lottery came along and as if by magic we got twenty million from the Lottery, seven million from the Commission for New Towns, we raised three million and we somehow fudged the remaining two or three million. And we’ve got one of the most beautiful theatres. The group that we invited to come in and manage it for us was a tiny little company called Turnstyle Theatre who had one theatre I think, down in Woking. It was Rosemary Squire and Howard Panter; and they so impressed me. I was in charge of that committee at that moment and they got the job. They’re now Ambassadors Theatre Company, the biggest in the country. And we’re still the showpiece theatre on their portfolio. It’s a beautiful theatre in the centre of Milton Keynes.

And what was their first production? Did you do a show early on there?

The first performance that hit that stage was our ‘All Change!’ play.

MAGGIE: They had a week before the professional opening; a week of community work.

ROY: Which is part of completing the process of building. We’d been building an audience for it through all the grass roots work that I’ve been describing, including our work in Stantonbury. The next huge thing we did was the National Theatre bringing ‘Oh What A Lovely War!’ It was a March production of this great play, performed in three tents and the weather was all squally and we had a huge adventure that week getting that up and running. I was able to tell the audience that ‘what you’re getting tonight in this canvas theatre is what you’re going to get in that’; and you could look a hundred yards across the park and there it was, still in its scaffolding, the new theatre coming out of the ground.

Throughout the eighties and nineties more and more people in different parts of the country are doing ‘community theatre’ – was there a burgeoning scene of conferences and meeting other practitioners and writers? Did it feel like this was a form of theatre that was in the ascendancy? And when did it all stop?

Well it wasn’t limited to what your prime interest is, which is community plays. We also created the Living Archive, which in its first days we called the National Centre for Documentary Arts. We published journals; we went to innumerable conferences; we held our own conferences including the Theatre of Fact conference at Stantonbury Theatre; and we created a professional T.I.E. company which lasted for seven years.

The Living Archive had a mission of turning people’s histories into any kind of art form, including drama and music and songs and fabric making and radio ballads and films; and that had a tremendous network impact I think.

But in terms of the theatre side did someone else come in? What happened to it?

Well we just changed our emphasis. We knew we had to carry this huge reservoir of acting, design, music, and dance ability in the community; all that experience had to keep growing and we did it by going into the Mysteries that I mentioned, along with ‘Lark Rise’ and ‘Candleford’, by Keith Dewhurst. Juniper Hill, which is where Lark Rise is, is only thirteen miles from where we live, where we’re sitting now. And so in a sense we were doing a local story by using Flora Thompson’s books but inspired by Keith Dewhurst’s treatments and the National’s version of it. And then we did the RSC’s ‘Nicholas Nickleby’, in four parts. I think Nicholas was thirty four nights of performance spread over a month. And worked on for a year.

MAGGIE: It’s a big commitment for amateurs.

ROY: So that’s nine hours, nine hours of performance.

And who was funding this?

Arts Council, Gulbenkian Foundation, Paul Hamlyn Foundation, Esme Fairbairn.

MAGGIE: Box Office, sponsorship and that lovely thing where you could double or triple your money through Challenge Funding, which doesn’t seem to exist anymore and was wonderful. You get a new sponsor and you get two thousand from them and then the Borough Council will double it and the ABSA, the association of British Sponsorship for the Arts would give you another match. So that two thousand gives you six.

ROY: But we always undertook to earn on Box Office a third of the total revenue costs of the project, and then we’d get a third through sponsorship, and a third through grants. We actually needed about sixty thousand towards the end.

Meanwhile Rib Davis was continuing with the documentaries; we’d handed them over and he did several.

MAGGIE: He did ‘Worker By Name’ which is the story of a man who lived in the square here in Stony Stratford; a man called Tom Worker.

ROY: And he did ‘A Particular Journey’. We’d done a day in the life of the whole population where everybody in the city was able to keep a diary for a day. It was a mass observation project, and we were very close in spirit to mass observation; it was an inspiration. Rib chose one particular testimony from that day and he dramatized it into ‘A Particular Journey’. He wrote other plays like ‘Nielsen’s Fifth’, which I directed,

MAGGIE: But that was before; that was early days, very early days.

ROY: So Rib continued with the community plays, and then he went national and did it for any town who wanted to pay him.

And did he continue with the rigour? Or did he start to put words into people’s mouths?

MAGGIE: I think he did if he was working for the Living Archive, because Roger (Kitchen) was a stickler; he was absolutely literal. Rib used the documentary but was much more of a playwright. From my memory it was a much freer structure, a much freer vocabulary you might say.

When you were writing and making your plays can you think of any particular texts that you read where you thought ‘this is interesting, this is the kind of work that I do’? Or did you see a community play that you particularly liked? Or did you think ‘nobody is really writing about how you put these things together, I should do that?’ Does it feel as though it’s an invisible craft?

ROY: Yeah I don’t think it’s been … I’ve not found it.

You’ve not found what?

The definitive account of what these plays were all about. I’ve had a number of articles published in Drama Magazine; in a German publication; in Dartington papers. And every time we created a programme for any one of our plays I wrote a Director’s Note which had my thinking fresh at the time when it was red hot on the page. So I’ve reflected on my job in bits and pieces and fragments; and also in the publications we created for the Living Archive which people subscribed to. It’s a pity we couldn’t keep those up but it was losing money; we were only charging two pounds. In those documents they do have something about what I think we were doing with our plays and why they were important and why they were so popular. But I don’t know of anybody else who’s really taken it on. I think there have been some reviews in The Guardian newspaper and Times Educational Supplement of things that we’ve done that I think have been very intelligent and have talked about our work.

MAGGIE: I think that in many respects this kind of work transmuted into what became known as ‘Tribunal Theatre’, like the work of Nicholas Kent at the Tricycle. We used to go and see a lot of those plays, but I feel they were so much more political. You (Roy) were not that political and I’m speaking for myself here, almost as an audience member. I always feel that your work was as a joiner together. It was in order to bring people together that you weren’t pointing out the most contentious elements; whereas I always felt with the Tribunal Theatre that’s exactly what they were doing. It’s setting one up against another; it’s almost creating a court scene. Our purpose was completely different to that.

It’s about building community …

It’s absolutely building; and maybe we stopped doing it when we felt that it’s time had happened; that we’d done that part, or Roy had done it anyway.

ROY: What do they call this other form of theatre?

Verbatim?

ROY: Yes, verbatim. Well before verbatim theatre, I mean you’d think David Hare had invented the form when he did that railway play ‘The Permanent Way’; you’d think he’d invented it. Peter Cheeseman did ‘The Knotty’, way back in the sixties, which is his Stoke Potteries railway play. We did ‘All Change!’, which was our railway play. And then along comes David Hare with ‘The Permanent Way’ and suddenly its big news, and it was no better than than ‘The Knotty’ and I would dare say no better than our play. And yet because it’s David Hare, because it’s the National Theatre, it gets adulation; and it gets attributed as a new invention.

MAGGIE: So maybe we have a little bit of a chip on our shoulder that we’re the poor relations. I don’t know; I don’t feel badly about it.

ROY: No; I don’t have any feelings about it. It’s like Alecky Blythe, with her stuff; the technique of listening to dialogue and just reproducing it instantaneously. These things which are fashionable come along and I think it wouldn’t be a bad idea if the mainstream tradition of it was recorded somewhere.

MAGGIE: It’s important to document it because in time somebody is going to reinvent it for their time. So it’s important to have an idea of what went on.

One thought on “An interview with Roy (and Maggie) Nevitt”