On Friday (September 1st) I met Baz Kershaw for the first time at the TaPRA conference in Salford. What I most wanted to know from this most insightful of writers and theorists of community theatre (and explorations of ‘the radical’) was whether or not the play that Medium Fair performed at my primary school, and which I still have some fuzzy pictures of in my head, was The Wizard of Oz. It was. And the year that I saw it, he was able to tell me, was 1975. Soon after this he and Medium Fair became involved in a new idea, a development of the relationship between community and theatre that his company had been exploring, a new idea that was to be pioneered by Ann Jellicoe. Baz told me he was going to see Ann next week.

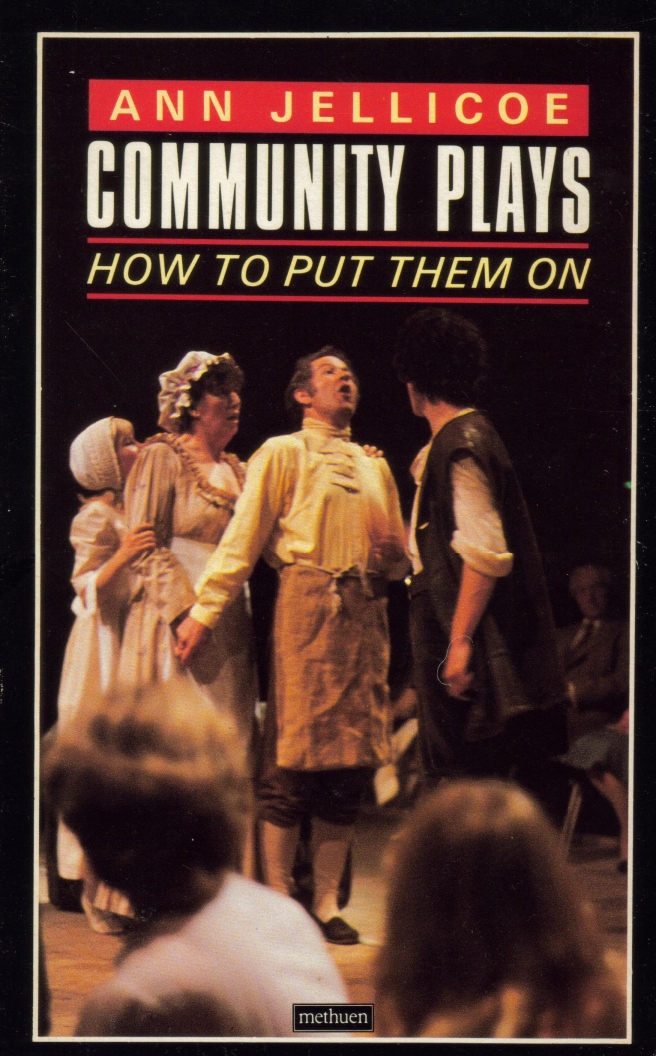

The day before (Thursday 31st August) I had given a ten minute ‘provocation’ to the Applied and Social Theatre group about the role of the writer in the community play. I had one image to accompany it – that of the cover of Ann’s book – and as soon as it came up it was obvious from the response that it was a text that many people knew and had a fondness for.

The day after getting home I discovered that Ann had died, through an obituary written in The Guardian. It feels like a death in the family; and that is, of course, what it is. As people whose work I know and respect have written of their feelings it is obvious that Ann was a woman whose ideas and work and energy and vision were hugely instrumental in the kind of theatre that they would themselves go on to make in their lives. The word ‘inspirational’ is often used in obituries, but it is only now that I truly understand what it means.

I would like to thank Ann. I first met her when I was twelve or thirteen; and she was a part of my life from then on until I left East Devon to go to university (to study drama, on her insistence). I was very lucky to have been involved not only as a performer in three community plays – The Tide, Colyford Matters, and The Western Women – but also in a small Theatre Games group that she set up. Alongside experimenting with the ideas of Keith Johnstone we were also lucky enough to have an early encounter with Boal’s Theatre of the Oppressed (although I don’t think it was Boal himself who worked with us), and to work on ideas for The Western Women with Fay Weldon, before Ann took over on writing the script.

My paper at TaPRA was partially a call to reignite the community play movement, because I still believe that it has the potential to create the most incredible and potent theatre, and that the act of making it can also be genuinely radical. Will Weigler responded to my words by saying how in Canada, after a visit by Jon Oram to create a community play with Dale Hamilton in Eramosa (which Jon himself talks about here) the idea quickly spread and many similar projects began to appear all over the country.

What an incredible legacy.

Here’s what I said.

I’m sure that many of you will recognise this book which was published in 1984 – the year that I went to university to study drama as a result of being in three of these community plays. About five seconds after that photograph was taken, in 1980, I entered the scene and stood just behind Alexandra, whose brother I used to play Subbuteo with.

And I’m aware that maybe my current research is actually all about trying to rectify in some way the fact that I arrived a little too late to be included in the picture.

I’m now a writer of community theatre – a term that I am happy to use – about thirty five plays in all, many of which have followed the Jellicoe model of a geographically bounded community and of a production technique where a writer is either invited or jettisoned into a community to create work with and alongside that community. And I have realised that there is very little discussion and very little in the literature about what the job of such a role entails.

So I’m reading the community plays that the first generation of community playwrights wrote to see what they were up to; although they’re not easy to get hold of. The V&A house the Community Play Archive and Database which contains materials on 215 community theatre projects through to 1999 although only half include the script of the play. Which has led me to contacting, where possible, the writers directly. ‘I’ve got a copy somewhere though I’ve moved house a few times’; ‘I think it’s with my ex-wife’; ‘You do realise this was the pre-Amstrad era so it’s typed up’. But they have been arriving, in jiffy bags, thousands of old pages kept together with rusting staples.

So far I have read around thirty of these scripts as I seek to uncover any generic affiliations that may allow me to unearth a prototype textual form. Most of the plays are set in a historical moment. And this link between the community play as a form and a heritage agenda that it appears to be closely connected to, is important I think in terms of where such plays often find themselves now.

In Theatres of Memory, Raphael Samuel locates the late 1960s as the explosion of do it yourself family and local history, having a particular appeal to the geographically and socially mobile, those who without the aid of history were genealogical orphans. And many of these scripts tap into that newly emerging enthusiasm, originating from a process of community research, often with the intention of identifying real people to base characters on.

Last week I was at a rehearsal of a community play for Barrow Hill written by Kev Fegan, whose first work in this field was with Welfare State. The project has been funded by the Heritage Lottery Fund. Looking through a database of HLF funding for projects under their ‘First World War: Then and Now’ scheme almost ten per cent stated they were planning to use community theatre in some way. Yet when I asked a senior member of the Strategy team how they viewed community theatre, given the extent to which they were funding it, I was told that ‘ I wouldn’t say anyone has more than a general view, which is about its usefulness as a way into heritage … we may not have much to say, I fear’.

When Arnold Wesker died last year none of the obituaries mentioned ‘Beorhtel’s Hill’, his community play for Basildon of 1989. By this stage Jon Oram had replaced Ann Jellicoe as the Artistic Director of the Colway Theatre Trust and had, he told me, approached Wesker to write a community play. And that one day, whilst walking through Basildon together Wesker had turned to him and said ‘Jon I can’t write this play … I can’t find one positive thing to say about this dumphole’. And that just as he said this a man came up carrying bin liners stinking of meths, breathed all over Wesker and said ‘the trouble is, when you wake up from the dream, Margaret Thatcher’s still alive’. At which point Wesker said ‘right, I’ve got the first scene, I’ll write it’.

The play features a narrator, who happens to be around 55, the same age as Wesker was when he wrote it. ‘Who are they?’ are his first words as he surveys a chorus of community characters; and the entire text is punctuated by the sense of bewilderment the narrator feels as he at once observes and evokes; with the plays’ final words being one last cry of ‘who are they? If only I knew who they were’. Wesker has been unable to learn a thing about this community whilst carrying out his work. But he has been completely aware of his exteriority; completely aware of the dangers of what Benjamin calls ‘ideological patronage’.

Now such artistic prerogative does exhibit a rather problematic stance, especially in a field which can, as Grant Kester suggests, fall prey to a ‘fetishization of authenticity in which only those artists who can claim an integral connection to a given community are allowed the ethical mandate to work with or represent it’. At a workshop last year at the ACTA centre in Bristol, which was asking how individual and community ownership of theatre happens, I brought up the question of the role of the writer. One director told me that they don’t use writers, but facilitators; to ensure a democracy of input; and another that in some ways he’d like to ban scripts along with any other artefacts of the event.

But what are we missing by not looking?

Richard Sennett, as Jen Harvie discusses in ‘Fair Play’, evokes the idea of ‘material consciousness’ as a key part of the craftsman’s skill, in which ‘all his or her efforts to do good quality work depend on curiosity about the material at hand’. And, importantly, ‘this curiosity is not simply about material objects but also material relations of production, including the material and social networks between people that the craftsperson engages in’.

These curiosities about the relations of production are clearly evident in the plays I have been reading by invited and commissioned writers. And this contextual understanding of their position and role appears to correspond to a range of narrative strategies. The plays are full of strangers who provoke and shatter and antagonise and question and confuse. Full of liminal characters who operate within and between different communal groups. And they constantly exhibit the interplay between the ‘geography’ of the public, as Sennett calls it, and the private domain. They are more often than not very self-reflexive texts, aware that the play they are writing is part of an event that contains a play.

In ‘Come Hell or High Water’ by Rupert Creed and Richard Hayhow, the community play for Bridlington of 1995, there is a conversation between an artist who is painting a seafront scene and a local fisherman:

‘You’ve got them ships dead right. Not sure about the flags though’, says the fisherman.

‘They add more colour. Balances the composition’, says the Artist.

‘They’re still wrong’, replies the fisherman.’ You’ve got them flying in the wrong direction’.

These writers may have been getting many things wrong, but perhaps their struggle to find a voice for a new form of theatre, and their confusion and awareness of their position in a wider social process, proclaiming the right for their individual voice as they also seek the acceptance of the collective, exhibits something of the projective, thrown together, and dissonant understandings of community that have become more recently theorised. As Claire Bishop suggests ‘a democratic society is one in which relations of conflict are sustained not erased’. And of course for a playwright conflict is the engine of narrative.

I want to briefly return to the question of heritage, because the community play found itself developing as a form at the same time that Robert Hewison and the heritage baiters, as Samuel calls them, saw heritage begin its ‘inflationary career’ commodifying the past and shoring up a crumbling national identity. And that it, heritage, became in Samuel’s words, ‘one of the principal whipping-boys of Cultural Studies’.

I wonder that if by neglecting to investigate the work that the texts of this first generation of community playwrights was doing that the community play movement allowed the subtleties, and potential of its work to be overlooked, and that the more easily observable signs of its production processes and its cross germination with a heritage discourse was therefore able to take precedence when identifying and codifying its formal qualities. That by remaining partially invisible to itself it was unable to follow Lyotards’ process whereby, ‘art is caught in an eternal treadmill of formal innovation and assimilation’ and instead found itself dissolving into some kind of quasi HLF franchise which has no real interest with, or understanding of, the idea of community theatre as an act of social provocation.

I am aware I may be trying to validate my practice. But the role of the writer in community theatre is a specific form of writing with specific challenges and the methods that writers have used when faced with these challenges – whatever their relationship with the communities they are working with – should be brought to light to ensure that the community play, as it moves through its second and into its third generation, is able to stand up for itself again as a hugely ambitious social experiment in the introduction of theatre into the public sphere.

And maybe we should love our writers a little more, especially when they fly the flags in the wrong direction.