This paper was presented at the Mental Health, Migration and Resilience: innovative applied arts based methodologies for research policy and practice conference at DeMontfort University on the 19th of October, 2019.

It was given in response to a project I had been involved in with the university which had led to the creation of a community play in Pune. The project, which was based around investigating notions of mental health resilience in a basti (slum) community, was a partnership between health and theatre practitioners and my work was primarily focussed on trying to ensure that the project moved away from any instrumentalist agenda and allowed the community to share their own stories to themselves.

Information on the wider project can be found here.

A 360 degree film which shows excerpts from the play (‘Suno Suno’) can be seen here.

I want to start by sharing some of the feedback that the researchers collected from some of the audience members who had seen ‘Suno Suno’, the final play that came out of the project:

‘I felt it was very good … I am actually feeling that how true it is! This all actually happens. It is only from your play that we are understanding what we are actually doing. Otherwise, we don’t pay attention to it nor realize it’.

‘Nothing like this has happened before … this is the first time that someone has come here, talked to us, asked us. So we also felt good about it and we also liked it … the play was really good … you have done it in a quite friendly manner. And this itself is an honour to us … It is our own story only; so there is nothing that we are angry at or anything. Everything was good indeed’.

‘… the things which we find difficult, you tried to show it in front of us, which motivated us … Everything was good’.

‘This all happens in the family. You are doing it to show the familial experiences. I am feeling good’.

‘It was needed here. Now the people understood how they live and what they do; this they have understood by themselves.’

It appears from these comments that the audience were happy with what they saw. That the play was accurate; that somehow it captured their lived reality; and there is a sense perhaps that this was unexpected. And perhaps most importantly that this re-presentation of their lived experience made them feel ‘good’. And yet there also seems to be the sense that the play was somehow to be learned from, that it should be viewed as some form of guidance; that it contained a message that the community were to respond to, to help them in some way. That it must have been there for a reason.

Now it’s true that the text of the play did have an element of a moralising finale; of a summing up of the importance of everyone helping each other. And although this was something that on a personal level I was ambivalent about – because of a dislike of didacticism in theatre, or at least a didacticism that doesn’t try to hide itself – it’s also clear that this was connected to a narrative form that is more traditional in India and which the audience may have been expecting. In fact a couple of days before the show I saw a modern piece performed by students and although it was in Hindi, and I couldn’t understand what was being said, the long final speech, the posture of the actor, and the accompanying music, made it clear that there was some message giving going on.

But I think that it wasn’t just the ending of the play that led many in the audience to see this as some form of consciousness raising activity, but also the very idea that a piece of theatre was being made about – and with – this community in the first place? Why on earth would anybody do that?

And this slight sense of bewilderment and confusion over purpose was palpable throughout pretty much the whole project and was, understandably, the central tension that was faced when theatre teams from different contexts met to work with social health teams from different contexts. On one hand the Western theatre practitioners said ‘we should view theatre as a research process; of a way of uncovering and learning from this basti community, of thinking as theatre as a new form of research language’. And on another hand – and there were many hands inbetween – there was a sense that the theatre was ultimately a way of sharing information, of acting as a dissemination tool, to communicate what had been learnt about the basti community even if the process of making the play was to be as collaborative as possible.

And I want to unpick this tension a little because as the applied arts become increasingly involved in work such as this, as the humanities are increasingly called upon to uncover new forms of knowledge, or rather to help dig into knowledge that exists within communities because it has perhaps developed better ways to have conversations with those communities, there is a danger, I think, of perhaps beginning to slide into previous traps that have been set when art meets social purpose.

Now let me back track a little. To 1948 and this line from The Declaration of Human Rights:

‘Everyone has the right freely to participate in the cultural life of the community, to enjoy the arts and to share in scientific advancement and its benefits’.

This statement links together ideas of culture, of community and of participation. It says that such a thing is a human right. And if you are a community artist, as I am, running a theatre company that works with people to make shows about their stories, then you could say that this statement also begins to suggest the importance of people coming together to not just observe but to create their own culture, their own art.

And it’s this word participation that is so important to community artists. In an innate understanding of the importance of people being given the space and the resources to make their own art.

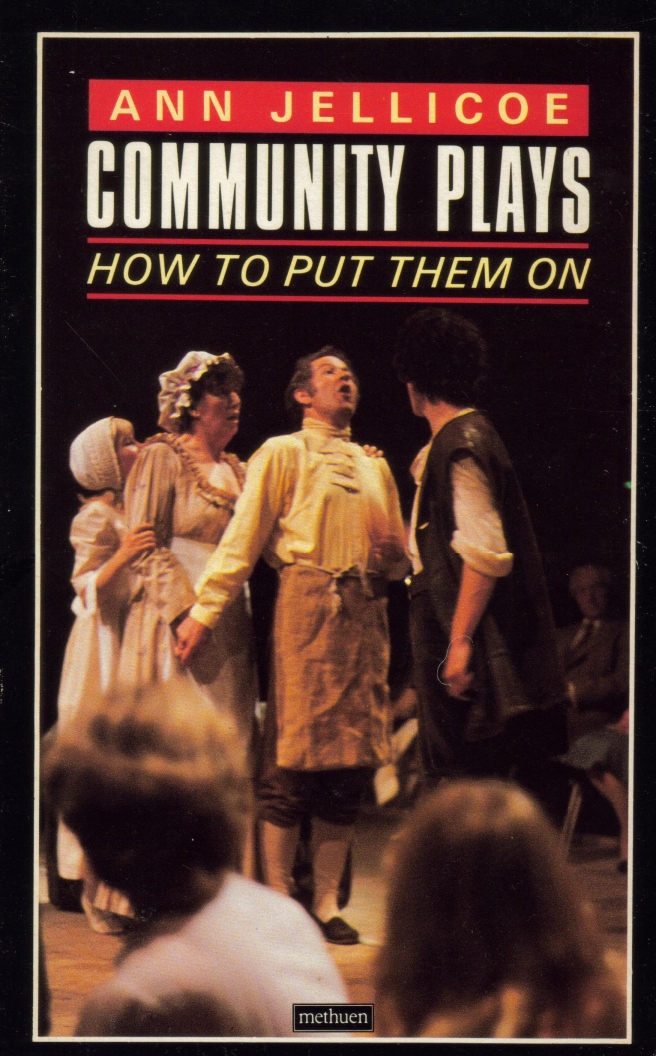

I run a theatre company, called Excavate, and for the last 20 years we have been making theatre with communities, generally communities of place and generally by creating work based on stories from the past from within those communities, yet stories that in their telling are usually informed by issues of the present. And at various times during our work, particularly during the early part of this century, we have found ourselves being asked to engage in all manner of projects that appeared less interested in theatre, and more interested in the fact that our practice was based on ideas of participation; that people liked working with us; and that therefore whilst doing our work we may be able to pass on some kind of message that the people who wanted us to work with them wanted to pass on. And these messages – which were usually aimed at working class communities – were also usually connected to things that these communities were seen to be lacking in; a so-called “deficit model of participation”.

And we said no to this. Our understanding of participation was a very democratic one, we wanted to come to the table as equals, and to decide what we would make together, knowing that some of us had different skills to share, which we would in a form of barter. You have primary knowledge, we have theatrical skills; how can we combine them and what do we want to make? Our impulse was very much allied to the origins of the community arts movement which was an inherently political project that saw participation as fundamentally about issues of power; of voice; of agency. And we felt uneasy about this interest in participation on a governmental level.

Because participation can mean many things; and can the term can be used to smuggle in many agendas.

This ‘ladder of citizen participation’ was created in 1969 by Sherry Arnstein who was writing about citizen involvement in planning processes in the United States and it was a model that the first generation of community artists referred to. At the bottom of the ladder is what Arnheim calls Manipulation and Therapy in which the aim is to cure or educate the participants. A plan is brought to the community and the job of participation is to achieve support for this plan through the process of public relations. And at the top end is Citizen Control where the entire job of planning and managing a programme or project takes place without outside interference. And it’s always worth, I think, when you declare that your work is participatory, checking in on this to see where the power really lies in these relationships. Particularly because of the danger of finding yourself on the rung of Placation, which may involve the setting up of committees to advise or plan but with the power holders having the ultimate right to judge the legitimacy or feasibility of the advice.

Participation is clearly then about power. But by the beginning of this century the word was beginning to mean something else. Participation was no longer seen as being a good in its own right, but was severed from a moral sense of democracy and exchange and was tied instead to external, governmental agendas.

Now we were utopian souls who wanted our work to make the world a better place; to bring different groups of people together and so we went to the University of Nottingham and asked them if they could work with us to find out if what we were doing was as socially useful as we blithely thought it was. And they asked us to spend three years working in an estate that was jam packed with all sorts of self-declared participatory interventionist programmes that were aiming to develop social capital and solve the many problems that had been ascribed to this particular place. And we were told, by all of the professionals that we met who were working there, that nobody would be interested in theatre; that nobody would want to get involved; that nobody would come along.

But they were wrong. Every show we made together – and we made three – was sold out.

This group of women – the Wigman Ladies, a splinter group from the Co-operative Women’s Guild – started off by being in a film in the first show, because they didn’t want to appear on stage, and then agreed to do this; and then helped us with the research for the final show. And at the end of these plays, and at the end of the project, people said things about what they had seen that were very similar to my initial quotes connected to the basti play.

And the university team that was working with us told us what we had done. Which was actually a list of what we had not done. They told us that we didn’t define people in the way that the other professional intervention teams did; as deficient, deprived, socially excluded, lacking in aspiration but rather as people who had stories to tell, whose histories were interesting, whose place in the world mattered.

That we did not expect everyone to be involved, but we did offer a range of ways in which people could be involved if they wished – maybe they could share a story, or help build a stage, or make some refreshments for the interval; or act or sing. That we were not interested in providing a service for clients, user groups or customers. That we did not engage in heavy duty discussion about the need for community, for positive local identities and for everyone pulling together in the face of adversity. That we were simply going to put on a performance which had a limited life.

When we began we were asked ‘can you help sort out the street lights and the dog mess?’ The community were so used to outside intervention that any form of engagement that might arrive without any desire to try and improve things in any way, but just to make something together, to be creative, was almost impossible to grasp. And we said ‘no. We can’t help you with anything. And we don’t want to. We just want to listen for now, and then work together to make some theatre about the things you’ve told us’.

There is a useful quote by James Thompson, who in writing about theatre in trauma and war contexts, (although the work we make is not in such arenas, it follows a similar principle), calls for ‘an ethnographic perspective that starts with the knowledges and practices within a community before diagnoses, treatments or performance techniques are assumed to be appropriate’.

Listening, hearing and respecting local ways of being and dealing with life militates against incoming theatre practitioners – or anybody else – initiating activities that can lead to more distress and harm, rather than the healing that is intended.

So, when I was asked if I would be interested in working on a project that was focussing on mental health and internal migration my first thought was ‘how is the theatre to be used? Is the project going to be a genuinely participative one, in which the use of theatre practices help us to listen; or is it going to be asked to pass on some kind of external message that has largely been constructed to serve a specific agenda?

And this question was a difficult one to deal with. We were working within a context where there is a tradition of using theatre to convey information, often health based, to basti communities. And working with organisations whose job is explicitly interventionist and who provide services and resources that are absolutely needed by the community. ‘What do you want us to say? What message do you want us to get across?’ was the first and second and third question that Swatantra, the Pune theatre company we were working with, understandably wanted an answer to. And when the company first went into the community and asked what kind of street plays the community would like them to do, it was initially asked to do work about sanitation issues; just as we had been asked in Nottingham to help with the street lights and dog mess. Both because the community saw the job of the theatre company as outsiders providing information, but also because it saw that through doing such a piece of work it could also proposition for resources that it felt was needed. The theatre had a very concrete and grounded social function.

I want to share another couple of quotes from the basti audience:

‘Such things are happening around here; that people cheat us. I like this part of the play.’

‘Such kind of things do happen. Yet, it feels good to watch the play’.

These are, I think, comments that reveal the value of making a show that was trying not to convey any kind of external message, even if the audience took one from it and even if the narrative form couldn’t quite help itself. Even though, as these quotes suggest, that what was being represented was not necessarily a positive or a celebratory thing – such as in this case being cheated – the fact of this being presented was in some way pleasurable and valuable. Because it was true; it was revealing and re-presenting in an artistic form a specific truth about that specific community, one which people knew and perhaps talked about but which wasn’t being represented anywhere else. And there were several comments like this. Even if the re-presented stories were not exactly as the community had told it, but were a version of it, the community – and the same thing happened during our work in the estate in Nottingham – responded as if something of the essence of what they had talked about had been successfully captured. And it was this that excited them, and made them feel ‘good’. And what is at the heart of this understanding is, I think, what the American critical theorist Nancy Fraser calls ‘recognition’.

Fraser argues that one of the ways in which people are marginalized and discriminated against is if their identities, languages, choices and ways of life are mis-recognized. This misrecognition then turns into active discrimination and injustice. Fraser argues that a politics of recognition is essential if people are to participate in society on an equal footing with others. Although she is also very clear that this must be linked to a politics of redistribution of resources.

This form of recognition, of people being allowed to express their own reality, is I think absolutely linked to the statement in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights that I shared at the beginning. That denying people the right to participate in the cultural life of the community is to deny them a voice and to deny them power. For preventing them from being heard is the first step to denying them other rights. And being heard requires you to find a way to communicate your experience. As Francois Matarasso has written, only if people have the potential to act as artists can they communicate what is meaningful to them in life. Only if they have the right to act as artists can they be heard as well as hear. Only if they have the right to act as artists can they express and defend their reality and their values on the same basis as others.

If the arts are going to be appropriated in some way by researchers working in other fields such as happened in this project then it must realise that theatre’s superpower lies in its potential to find ways to give people their own voice. That it must use theatre to let people reveal their own knowledge and communicate their own experience for us to listen to so, that they are not simply at the mercy of other people who have greater power to make definitions and diagnoses for them.

This is surely healthy, for individuals and for communities. And before I end I want to say a little more about the potential of this work as a community building exercise. The basti project was, like most of the work I am involved in, connected to a community of place. And place is not simply a physical location. A location becomes a place by virtue of the meanings that people attribute to it. It becomes meaningful through what happens there, the social interactions and networks that are established, the cultural and political actions that are taken and experienced, the memories and stories that are built up about it.

Doreen Massey writes of place as an ‘event’. Rather than place being fixed, it is always in formation, always being made, unmade, and changed. It is ‘throwntogether’, the result of ‘the challenge of negotiating a here-and-now… drawing on a history and a geography of thens and theres’. If place is always an event, and the very fact that this project was partly dealing with the challenges of the fragility of sense of place that internal migration causes, then community theatre can perhaps be seen as a place-making process in the way that it brings people together in a collective creative effort, as producers and audience. It is in these moments of publicly shared recognition, of re-presentations of grounded experience, that place may be reinvested with local meaning as a bulwark against an identity forming process that is being led by external agendas. And if these external agendas become too powerful or are not contested then the dangers of misrecognition of that place, and of those who live within it, with all of the dangers this poses, is very real.

And of course community theatre offers the potential to change associational patterns in the neighbourhood. New friends can be made, new talents can be discovered, and the performance itself can become a new shared memory. The material, geographical location becomes, for those who are involved as either audience or participants, a little more imbued with public meanings – meanings built from the life experiences of those who live there, told in language that is familiar in contrast to those narratives of local experiences that the media and politicians may turn into bureaucratic and sensationalising texts.

I want to end with one last quote from the audience, or rather an exchange between the interviewer and an audience member:

I: And do you feel that such kind of performances should happen?

R: Let us see. Let us see after a month or two if needed, then we can have another show

I: Will the people get help from this play? Will they able to understand such kind of situations also take place? Or do they understand how they have also overcome their own critical situations, likewise that are shown in the play?

R: Yes. People would be able to understand quite a bit of it. If we add some more content in it, they will understand it. But doing it just for one time, won’t help.

In this, I think, we come back to the tension over the purpose of the play; in the need for some kind of message and the idea of some kind of learning ultimately to have taken place. But also that a sense of ownership is beginning perhaps to develop – ‘if we add some more content in it’. And also, that this needs to be just the beginning of a process. That the idea of a space where people are given free rein to share stories that otherwise may not have been shared must continue. And we must be ready to find ways to hand over more power still and in doing so there is much to be gained. The knowledge we learn from observing and watching and listening should not just come from the stories that we are told, and the help that the community gives us with the script and the responses to what they have seen, but by the kind of artistic languages that people may reach for or create themselves to express what they want to express. The forms in which they speak may tell us as much, if we learn how to look, as the message that is contained within them.

Bolsover Bingo – Excavate – for the First Art programme funded by Creative People and Place and Places

Bolsover Bingo – Excavate – for the First Art programme funded by Creative People and Place and Places